On behavioral genetics, the geometry of Indian cities, Snowflake and data engineering, hardware-software symbiosis, and Chinese state capitalism

Interesting Links: September 27, 2020

-

Interesting paper surveying behavior genetics. The forthcoming version of this paper is available on the author’s website here.

On heritability:

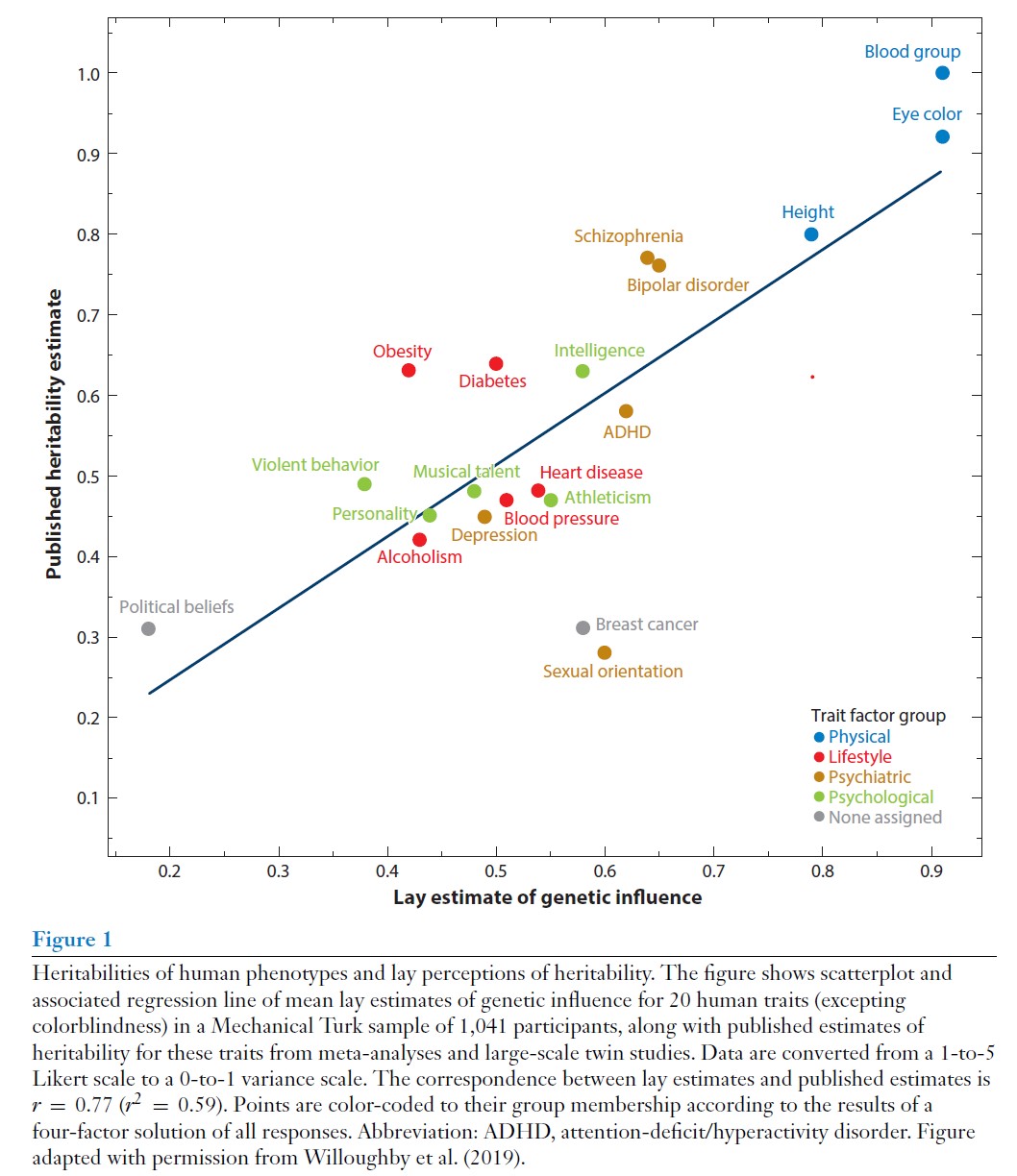

According to this survey of the research, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are quite highly heritable. And not shown on this graph, but autism is noted to be as heritable as height (~90%). And also noted is that “another phenotype with nearly perfect heritability already in childhood is executive functioning, defined as a general ability to regulate attention.”

People tend to think obesity and diabetes are less highly heritable than they actually are, while people tend to think incidence of breast cancer and sexual orientation are more heritable than they actually are. And somewhat surprisigly, intelligence appears more inheritable than, say, musical talent or athleticism. But I’m not sure of the confidence intervals here, so most of these suggest a similar ~50% average heritability.

Studying identical twins, the author summarizes the research as: “You only have one life to live, but if you rewound the tape and started anew from the exact same genetic and environmental starting point, how differently could your life go? Overall, twin research suggests that, in your alternative life, you might not have gotten divorced, you might have made more money, you might be more extraverted or organized—but you are unlikely to be substantially different in your cognitive ability, education, or mental disease.”

Discussing the slightly differing results in DNA-based estimates of heritability vs. twin studies, the author notes: “the continued gap between DNA-based estimates of heritability and estimates from twin/family studies means that the latter might still be overestimating heritability due to faulty assumptions. But it is no longer reasonable, contra some predictions, to expect that advances in human genomics will reveal that the heritability of psychological phenotypes is entirely illusory.”

On Genome-Wide Association Studies:

The effect size of individual genetic variants in relation to psychological and behavioral traits is quite small (R2 < 0.1%). Given this, the author notes that “it is clear that psychological studies that interrogated single candidate genes, such as 5HTTLPR (a variant of the serotonin transporter gene), were massively underpowered statistically, and their results were false positives (Chabris et al. 2012). This methodological flaw—insufficient statistical power—is even more pronounced for studies of candidate gene × environment interaction (cG × E), such as studies of the interaction between 5HTTLPR and life stress on depression (Caspi et al. 2003). As early as 2011, analysts warned that most positive cG × E findings were false discoveries (Duncan & Keller 2011). In the next decade, subsequent review and editorial statements about candidate gene and cG × E findings warned that “it now seems likely that many of the published findings of the last decade are wrong or misleading and have not contributed to real advances in knowledge…”

On gene-environment interplay:

On how the environment matters, the author notes: “Whereas more basic cognitive abilities like executive functioning and processing speed are nearly perfectly heritable even in childhood (Engelhardt et al. 2015) academic skills in reading and mathematics, which are the direct targets of instruction, show substantial shared environmental variance, even when all participants are drawn from schools in a single geographical area (Engelhardt et al. 2019, Rimfeld et al. 2018b).” To put it concisely - “…social privilege is replicated across generations via environmental mechanisms.”

-

Sara Hooker at Google Brain writes about the hardware lottery. Fantastic paper. With almost all commercial resources today towards deep neural net type architectures, are we building a ladder to the moon? Doomed to fail in the quest for understanding and modeling human intelligence.

She talks about the observation that a research idea often wins because it is compatible with available software and hardware and not because the idea itself is superior to alternative research directions.

Producing a next-gen chip typically costs $30-80 million and 2-3 years to develop. Thus, in hardware, we tend to see a much more closely guarded research culture. Machine learning researchers, without levers to influence hardware development, tend to treat hardware as a sunk cost to be worked around rather than shaped.

She uses deep neural nets itself as an example of a research idea developed multiple times since the 1960s but did not get widely accepted for another three decades in large part due to incompatible hardware (i.e., the rise of the general purpose CPU). She notes that Hinton & Anderson back in the 1980s had already proposed the need for hardware that supports massive parallelism. “Without a consumer market, there was simply not the criticla mass of end users to be financially viable.” And it only became viable with the development of GPUs as we well know.

She also makes a similar point with software - that the use of LISP, favored by the early AI community, which led to more research on reasoning and expert systems, while neural nets couldn’t be easily explored. However, here the direction of causality isn’t that obvious to me.

She goes on to discuss the rise of TPUs and how the current and probably future directions of hardware development are informed by currently popular research directions. She notes that “there is still a separate question of whether hardware innovation is versatile enough to unlock or keep pace with entirely new machine learning research directions.” She uses capsule networks as an example - a new computer vision architecture that is difficult to train on current hardware.

She doesn’t extensively discuss the role of FPGAs however in this quest for potentially iterating on hardware development as well. See my earlier post here linking to Jane Street’s discussion of FPGA development today. But she does however note approaches to reduce this cost of chip development - reinforcement learning to optimize chip placement, and renewed interest in FPGAs and CGRAs (coarse-grained RAs). And she observes that “coding even simple algorithms on FPGAs remains very painful and time consuming.”

But on to the main point of the paper, quite clear by now - we know we are very far away in ML research from the type of intelligence humans demonstrate. But our hardware and software tools (with a particular emphasis on hardware) are virtually all geared towards research directions like deep neural nets - with extensive, immediate commercial use cases but ultimately flawed in the quest to understand and model human intelligence. The solution when it comes to hardware is tricky and not evident, but the author essentially suggests more public funding. But on the software front, clearly software needs to do more work. As she says, “we have neglected efficient software throughout the era of Moore’s law, trusting that predictable gains in compute would compensate for inefficiencies in the software stack.”

For more reading, in a similar vein, three researchers at Nesta write about the narrowing of AI research.

-

Good paper in the American Economic Review on “cities in bad shape: urban geometry in India”. The author studies the geometry of Indian cities and investigates the causal economic implications of this geometry.

The author measures the compactness of cities. For example, controlling for city area, the average linear distance between any two points in the city is 27 percent longer in Kolkata than it is in Bangalore.

Unsurprisingly, the author finds lower rents in less compact cities. However, interestingly, the author finds that less compact cities are associated with higher wages. According to the author’s model, the relationship between compactness and wages should essentially depend upon whether households or firms value compactness the most.

The most compact cities with a large population, according to the author’s methodology, include cities like Rajkot (normalized disconnection of 0.924), Lucknow (0.943), Nashik (0.948), Jaipur (0.948), and Hyderabad (0.961). Pune is somewhere in the middle (0.982) as is Baroda (0.986). Bangalore and Ahmedabad are deemed as one of the less compact cities (1.023). The least compact cities include Asansol (a staggering 1.625), Kolkata (1.128), Surat (1.111), and surprisingly Chennai (1.081) and Mumbai (1.071).

Mumbai’s trend is interesting, if predictable: a disconnection index of 1.261 in 1950 to 1.14 in 2000 to 1.072 in 2010.

-

Snowflake filed an S-1 last month, which I didn’t have time to dig into among the flurry of S-1 filings last month. A Snowflake deep dive is exactly this. It also gives a very good introduction to tbe basic problems & their evolution when it comes to data warehousing/processing for Business Intelligence activities (a core problem that Snowflake attempts to help with).

The history is interesting. Founded in 2012 by ex-Oracle data architects, it operated in stealth for a few years, finally launching the platform publicly in late 2014 as a Data Warehouse-as-a-Service running on AWS. Azure and Google Cloud were added only in mid-2018 and mid-2019 respectively. The Board of Directors includes many industry-aware high-level folks from ServiceNow, VMWare/Dell/AMC, BMC Software, Adobe, and Symantec.

So what does Snowflake do? “It is an analytical database that has SQL querying capabilities over the entire Data Lake.” It allows for SQL quering over both structure (relational) and semi-structured (NoSQL) data. Under the hood, it is still all columnar data stores. Further, Snowflake is also similar to Hadoop-as-a-Service so you can run analytical tools directly within its distributed compute. You can run distributed Spark jobs directly inside Snowflake’s distributed compute.

Now so far all the cloud providers have also moved in this direction & are directly offering the same data lake & data warehousing & analytical capabilities. The one obvious advantage of Snowflake is that it works with all three major cloud providers, so it helps the customer to not be locked-in to any one cloud provider and thus cede all leverage to the cloud provider.

Another clear benefit of the platform is that “it provides frictionless and governed data access so users can securely share data inside and outside of their organizations, generally without copying or moving the underlying data.” That this is without having to copy the data is impressive indeed as an off-the-shelf offering.

Additional details about the financials themselves is available in this other teardown by Public Comps and this analysis of the S-1 by The Generalist.

-

Good podcast with Adam Tooze on China. Much of it is quotable - here’s one long excerpt:

[Neumann] described what happens to capitalist States when they get caught up in a logic, which he took to be characteristic of the 20th century, which is oligopolistic, monopolistic rule. The international system of free trade results from monopoly. And the result of that is protectionism and tariff war, and, ultimately in Hobson’s view, a race towards imperialist competition and war. Continue that line of thought and ask yourself, “Okay, so what does monopoly do and what do oligopolistic structures do to the domestic political structure?”

It systematically subverts principles of representation. It begs the question of who has power and what is the role of the state in relation to those interests. Because properly understood liberalism clearly isn’t premised on the absence of the state, its premised on a well-ordered set of relationships between individuals, the law and various types of representation. That structure is not necessarily robust if economic power becomes monolithic. There are ways of taming that by way of corporatism, in which you have an organized representation of economic interests. But you can also imagine systems in which it can become a sort of destructive set of flywheels of extremely explosive dynamics of gigantic interest groups contending with each other more or less in an unmediated direct form interest on interest.