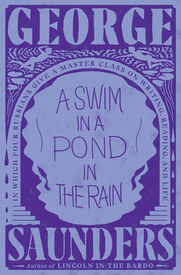

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain

In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life

by George Saunders

Completed: May 25, 2021- Writing

- 410 pages

- ISBN: 9781984856029

- Goodreads page

The whole experience of reading fiction might be understood as a series of “establishings” (“the dog is sleeping”), stabilizations (“he is really sleeping deeply; so deeply that the cat just managed to walk across his back”), and alterations (“Uh-oh, he woke up”).

But there is nothing enduring in this world, and that is why even joy is not as keen in the moment that follows the first; and a moment later it grows weaker still and finally merges imperceptibly into one’s usual state of mind, just as a ring on the water, made by the fall of a pebble, merges finally into the smooth surface.

Nikolai Gogol, The Nose

Look at life: the insolence and idleness of the strong, the ignorance and brutishness of the weak, horrible poverty everywhere, overcrowding, degeneration, drunkenness, hypocrisy, lying— Yet in all the houses and on all the streets there is peace and quiet; of the fifty thousand people who live in our town there is not one who would cry out, who would vent his indignation aloud. We see the people who go to market, eat by day, sleep by night, who babble nonsense, marry, grow old, good-naturedly drag their dead to the cemetery, but we do not see or hear those who suffer, and what is terrible in life goes on somewhere behind the scenes. Everything is peaceful and quiet and only mute statistics protest: so many people gone out of their minds, so many gallons of vodka drunk, so many children dead from malnutrition— And such a state of things is evidently necessary; obviously the happy man is at ease only because the unhappy ones bear their burdens in silence, and if there were not this silence, happiness would be impossible. It is a general hypnosis. Behind the door of every contented, happy man there ought to be someone standing with a little hammer and continually reminding him with a knock that there are unhappy people, that however happy he may be, life will sooner or later show him its claws, and trouble will come to him—illness, poverty, losses, and then no one will see or hear him, just as now he neither sees nor hears others. But there is no man with a hammer. The happy man lives at his ease, faintly fluttered by small daily cares, like an aspen in the wind—and all is well.

Anton Chekhov, Gooseberries

I quite enjoyed this book - both, the short stories that the author chose, and his thoughts on those stories and writing in general. Perhaps if I were actually a serious writer, I’d get more out of this book. So the relatively low rating is more a reflection of my shortcoming than that of the author. The book is a collection of seven Russian short stories (3x Chekhov, 2x Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Gogol) & the author’s ruminations on them.

…this is a resistance literature, written by progressive reformers in a repressive culture, under constant threat of censorship, in a time when a writer’s politics could lead to exile, imprisonment, and execution. The resistance in the stories is quiet, at a slant, and comes from perhaps the most radical idea of all: that every human being is worthy of attention and that the origins of every good and evil capability of the universe may be found by observing a single, even very humble, person and the turnings of his or her mind.

As long as there’s love, there’ll be people who aren’t loved. As long as there’s wealth, there’ll be poverty. As long as there’s excitement, there’ll be dullness. The story’s conclusion, essentially, is: “Yes, that’s how it is in this world.”

“The Darling” is about a tendency, present in all of us, to misunderstand love as “complete absorption in,” rather than “in full communication with.”

I’ve worked with so many wildly talented young writers over the years that I feel qualified to say that there are two things that separate writers who go on to publish from those who don’t.

First, a willingness to revise.

Second, the extent to which the writer has learned to make causality.

Making causality doesn’t seem sexy or particularly literary. It’s a workmanlike thing, to make A cause B, the stuff of vaudeville, of Hollywood. But it’s the hardest thing to learn. It doesn’t come naturally, not to most of us. But that’s really all a story is: a series of things that happen in sequence, in which we can discern a pattern of causality.

For most of us, the problem is not in making things happen (“A dog barked,” “The house exploded,” “Darren kicked the tire of his car” are all easy enough to type) but in making one thing seem to cause the next.

This is important, because causation is what creates the appearance of meaning.

“The queen died, and then the king died” (E. M. Forster’s famous formulation) describes two unrelated events occurring in sequence. It doesn’t mean anything. “The queen died, and the king died of grief ” puts those events into relation; we understand that one caused the other. The sequence, now infused with causality, means: “That king really loved his queen.”

Douglas Unger, one of my professors at Syracuse years ago, offered a model for how people communicate in the world.

When two people are talking, Doug suggested, each has a cartoon bubble overhead, full of his or her private hopes and projections and fears and preexisting worries and so on. Person A talks, Person B listens, waiting to respond, but as what Person A is saying passes into Person B’s cartoon bubble, it gets mangled.

Say Person B’s bubble is full of guilt because, after she forgot to call her mother on her birthday, her brother chidingly texted her about it. When Person A says, “I have to give a speech next week,” Person B, thinking of the rude things her brother just texted, replies (out of her bubble), “People can be so harsh.” Person A, his bubble full of anxiety about this forthcoming speech, hears: “It’s true, you’ll probably blow it,” and frowns. Person B thinks, “Oh, great, Person A is frowning at me because he sees that I’m the kind of jerk who forgets her mother’s birthday.”

There is no world save the one we make with our minds, and the mind’s predisposition determines the type of world we see.

A woman who lives in a tiny ranch house, obsessed with the fact that her grass is dying, goes to Versailles and is impressed, mostly, by the lawns.

A dominated guy in a bad marriage goes to a play and can’t get over how much his wife is like Lady Macbeth. Such is life.

No, really, says Gogol, such is life.

I think, therefore I am wrong, after which I speak, and my wrongness falls on someone also thinking wrongly, and then there are two of us thinking wrongly, and, being human, we can’t bear to think without taking action, which, having been taken, makes things worse.

If you’ve ever wondered, as I have, “Given how generally sweet people are, why is the world so fucked up?,” Gogol has an answer: we each have an energetic and unique skaz loop running in our heads, one we believe in fully, not as “merely my opinion” but “the way things actually are, for sure.”

The entire drama of life on earth is: Skaz-Headed Person #1 steps outside, where he encounters Skaz-Headed Person #2. Both, seeing themselves as the center of the universe, thinking highly of themselves, immediately slightly misunderstand everything. They try to communicate but aren’t any good at it.

Hilarity ensues.

Most of the evil I’ve seen in the world—most of the nastiness I’ve been on the receiving end of (and, for that matter, the nastiness I, myself, have inflicted on others)—was done by people who intended good, who thought they were doing good, by reasonable people, staying polite, making accommodations, laboring under slight misperceptions, who haven’t had the inclination or taken the time to think things through, who’ve been sheltered from or were blind to the negative consequences of the belief system of which they were part, bowing to expedience and/or “commonsense” notions that have come to them via their culture and that they have failed to interrogate. In other words, they’re like the people in Gogol. (I’m leaving aside here the big offenders, the monstrous egos, the grandiose-idea-possessors, those cut off from reality by too much wealth, fame, or success, the hyperarrogant, the power-hungry-from-birth, the socio- and/or psychopathic.)

All book cover images are from Goodreads unless specified otherwise.